Black Minqua

Chinklacamoose (Clearfield, Pennsylvania) and the Great Shamokin Path

Who Were the Black Minqua?

The Black Minqua were an Indigenous community associated with the Susquehannock (an Iroquoian-speaking nation) whose settlements extended along the Susquehanna River and into parts of central and western Pennsylvania.

European colonists adopted the Lenape term Minqua, often translated as "stealthy" or "treacherous," though such interpretations reflect colonial-era perspectives and conflict narratives. Over time, historical sources distinguished between "White Minqua" (generally referring to the main Susquehannock population) and "Black Minqua," a designation used for groups living farther northwest in the West Branch Susquehanna region.

The Black Minqua established a village at Chinklacamoose—a name recorded in multiple spellings—located at what is now Clearfield, Pennsylvania.

The Great Shamokin Path

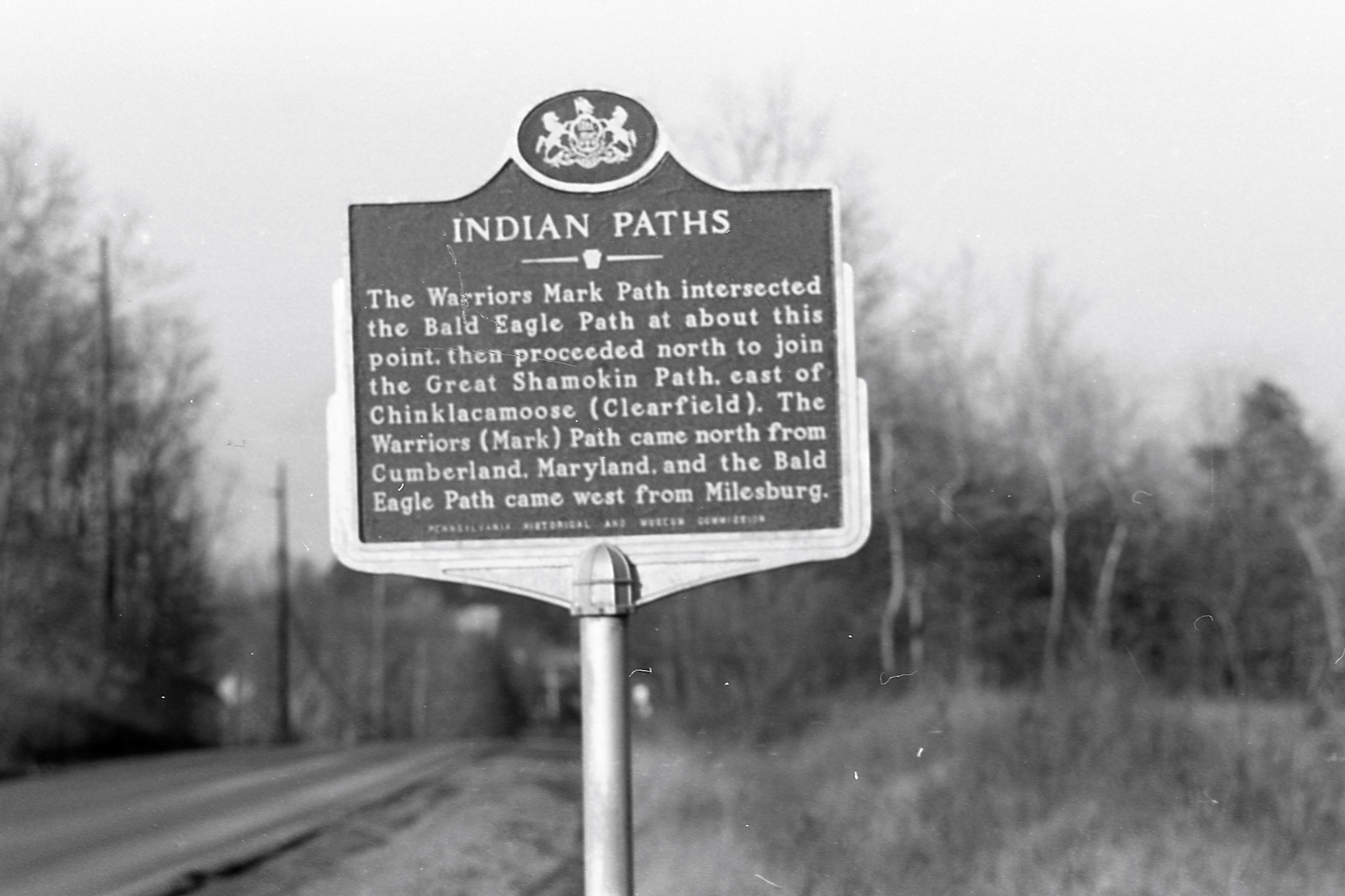

Chinklacamoose was situated along the Great Shamokin Path, one of the most important Indigenous travel and trade routes in Pennsylvania. The path connected the village of Shamokin (present-day Sunbury) along the West Branch of the Susquehanna River to Kittanning in the Allegheny River Valley.

Today, portions of this historic route correspond roughly to U.S. Route 322, though the original trail followed river contours and seasonal travel patterns. Indigenous paths such as this formed the backbone of regional trade networks, diplomatic travel, hunting expeditions, and communication long before European roads were built.

Settlement and Daily Life

Historical and archaeological accounts describe Chinklacamoose as a fortified village. It was reportedly enclosed by a circular earthen embankment and palisade of upright wooden posts. Such fortifications were common in periods of regional conflict and may have served both defensive and symbolic purposes.

Within the enclosure, families lived in structures constructed from saplings bent into frames and covered with bark or mats. Communities of twenty to forty residents likely occupied the site seasonally, depending on agricultural cycles, hunting conditions, and regional alliances.

The surrounding river valley provided abundant resources. The Black Minqua traveled the West Branch of the Susquehanna in dugout canoes and relied on fishing, eel harvesting, freshwater mussels, hunting, and agriculture. Controlled burning of vegetation—sometimes called "clearing"—was a common Indigenous land management practice used to improve soil fertility, encourage game, and maintain open travel corridors. Local tradition holds that the name "Clearfield" may derive from such practices.

Historical Context

By the seventeenth century, Susquehannock and related communities were deeply affected by warfare, epidemic disease, and expanding European trade networks. Power struggles involving the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), colonial governments, and shifting alliances reshaped much of Pennsylvania's Indigenous landscape.

Over time, many Susquehannock-descended communities were displaced or absorbed into other Indigenous nations. Today, knowledge of the Black Minqua survives primarily through archaeological findings, colonial records, and oral histories connected to the broader Susquehannock and regional Indigenous traditions.