Overview

The Great Minquas Path—sometimes called "The Great Trail"—was a major 17th-century Indigenous trade route that connected the Susquehanna River near present-day Conestoga to the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers near modern Philadelphia. The approximately 80-mile east–west corridor passed through what is now Chester County, including the area around present-day West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Long before European settlement, this path formed part of a broader network of Indigenous travel routes used for trade, diplomacy, seasonal migration, and communication. It later became central to the colonial fur trade between Native nations and Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers.

The Minquas and the Susquehannock

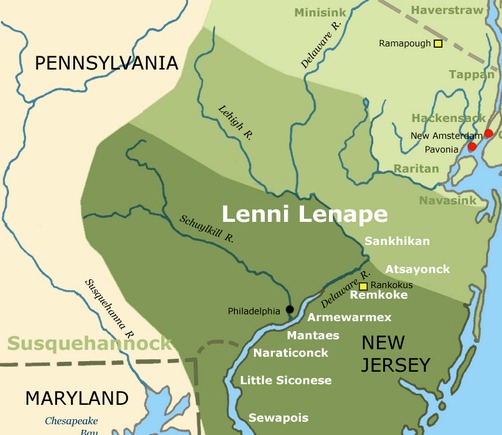

The term "Minquas" was used by Dutch and Swedish colonists and derived from a Lenape word often translated as "stealthy" or "treacherous." It referred primarily to the Susquehannock people, a powerful Iroquoian-speaking nation whose main settlements were along the Susquehanna River. The English later referred to them as the "Conestogas," after their principal town.

In the early to mid-1600s, the Susquehannock were dominant participants in the regional fur trade and were militarily powerful. Control of trade routes such as the Great Minquas Path allowed them to exchange furs—especially beaver pelts—with European traders along the Delaware River.

Colonial Competition Along the Path

The Dutch began organized fur trading in the 1620s and referred to the route as Beversreede ("Beaver Road"). Around 1633 they constructed Fort Beversreede near the mouth of the Schuylkill River to secure access to trade.

The Swedish colony of New Sweden, established in 1638, sought to compete with Dutch trade interests. Governor Johan Björnsson Printz built Fort Nya Vasa in 1644 near Cobbs Creek, where the trail crossed into the Delaware River watershed. In 1648 the Swedes constructed a blockhouse near Fort Beversreede, escalating tensions. The Dutch reasserted control in 1655 under Peter Stuyvesant, incorporating New Sweden into New Netherland. English forces then took control in 1664.

These colonial rivalries were layered onto preexisting Indigenous political dynamics. In the 1630s and 1640s, the Susquehannock expanded influence in parts of the Delaware Valley, reshaping regional power relationships with Lenape communities and other neighboring nations.

Disease, War, and Displacement

By the late 17th century, epidemic disease, sustained warfare—including conflicts with Maryland colonists and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy)—and shifting trade alliances severely weakened the Susquehannock. Survivors consolidated in smaller communities, intermarried with other Native groups, or migrated.

In December 1763, a vigilante group known as the Paxton Boys massacred 20 Conestoga people in Lancaster County. This event marked one of the most tragic episodes in Pennsylvania’s colonial history and effectively ended the visible presence of the Susquehannock community in the colony, though descendants and cultural legacies persisted.

Legacy and Modern Landscape

Segments of the Great Minquas Path influenced later colonial roads. Portions of Strasburg Road in Chester and Lancaster Counties generally follow the historic route. Pennsylvania historical markers in Philadelphia, Delaware, Chester, and Lancaster Counties commemorate the trail’s significance.

Today, the path stands as a reminder that Pennsylvania’s infrastructure—roads, trade corridors, and settlements—often developed along far older Indigenous travel networks. Understanding the Great Minquas Path helps place colonial history within its deeper Indigenous context.